32 European police forces attack encryption (again)

In a ‘Joint Declaration’, 32 European police forces have (yet again) attacked the increasing deployment of end-to-end encryption (such as on Meta’s three platforms WhatsApp, Messenger and soon Instagram.) The UK’s National Crime Agency has made a particular effort to publicise it.

This is how powerful policy stakeholders (like law enforcement and big business) often win arguments. They never, ever give up, repeating the same arguments ad nauseam — over decades if necessary — regardless of any evidence which emerges.

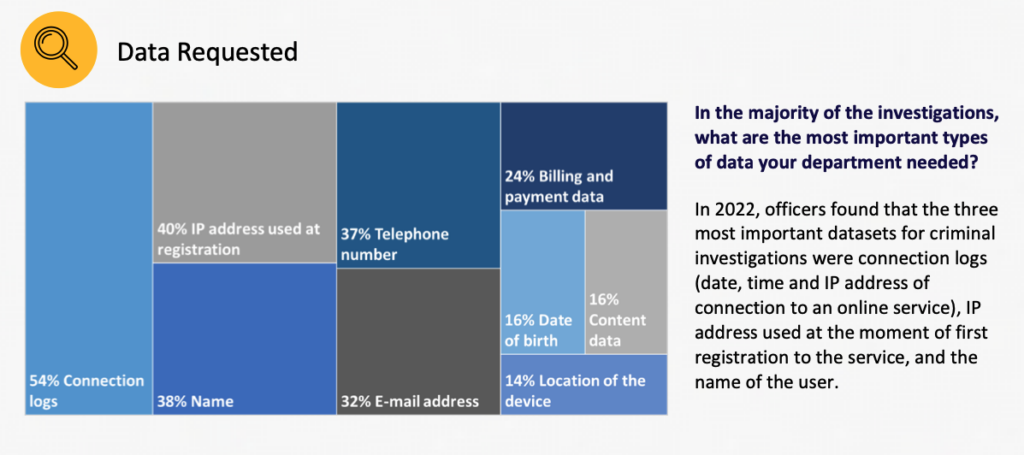

Even intelligence insiders have acknowledged that, contrary to scare stories about surveillance “going dark”, the widespread use of connected tech has made this century a ‘Golden Age of Sigint’ (signals intelligence). And last year, Europol reported that just 16% of the electronic evidence it needed access to was “content data”, the type usually affected by end-to-end encryption.

European police have gathered evidence from tens of thousands of encrypted mobile phones (using EncroChat) which has led to thousands of prosecutions (with important human rights and evidential quality questions raised.) What lessons can we learn from that?

The law enforcement declaration makes the same “binary choice” error they accuse others of. “Companies will not be able to respond effectively to a lawful authority.” To do what? “Nor will they be able to identify or report illegal activity on their platforms.” Wildly inaccurate. “As a result, we will simply not be able to keep the public safe.” 💩 This would be a lot more productive debate if police chiefs would acknowledge even the smallest amount of nuance, rather than shroud-waving.

What types of systems can be built which protect vulnerable people and privacy? Meta claims it is doing this; where are the independent evaluations of their and other companies’ claims? Shouldn’t the UK govt make use of the sterling research work it has funded by examining this question?

An independent review in 2022 by Business for Social Responsibility for Meta “found that expanding end-to-end encryption enables the realization of a diverse range of human rights and recommended a range of integrity and safety measures to address unintended adverse human rights.” Meta committed to “implementing 34 of the [45] recommendations, partly implementing four, assessing the feasibility of six and taking no further action on one.” It would be useful to know what progress has been made on this.

The distinguished and sadly recently deceased Prof. Ross Anderson published two powerful analyses of these issues in the last 18 months alone. And in February, the European Court of Human Rights determined:

Weakening encryption by creating backdoors would apparently make it technically possible to perform routine, general and indiscriminate surveillance of personal electronic communications. Backdoors may also be exploited by criminal networks and would seriously compromise the security of all users’ electronic communications. The Court takes note of the dangers of restricting encryption described by many experts in the field. (par 77)

Societies would be much better off — rights respected, criminals investigated and vulnerable people protected — if the policing and intelligence organisations pushing this agenda would learn a little from their almost 50 years of failing to get end-to-end encryption banned 🫠

See also

No One Should Have That Much Power, by Web standards expert Mark Nottingham