Recent developments in digital competition

By Ian Brown. Last updated: 7 May 2025

Thanks to Open Society Foundations for commissioning this series of briefings on digital competition developments in key jurisdictions — Brazil, China, the European Union, India, UK and US (with a brief note at the end on South Africa).

Issues at stake

The six largest US-based tech businesses (and indeed firms in the US S&P 500 stock index – Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft and Nvidia) are world-historically valuable businesses, now collectively worth around $15tn. China has several more tech giants each worth hundreds of billions of dollars, including Alibaba and Tencent. The ten largest companies in the MSCI All Country World Index — all American — make up around one-fifth of the index, well above the dotcom era peak of 16.2% in March 2000, and the highest level in its 30-year history.

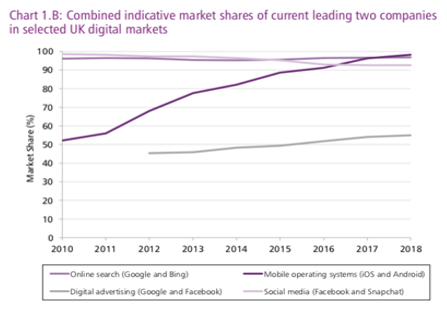

For many digital services, one or two companies already have an extraordinarily high share of significant numbers of national markets. The Furman review estimated this in the UK at close to 100% for mobile operating systems and online search, with social media above 90%:

The European Parliament noted “with regret that one search engine that has over 92% of market share in the online search market in most of the Member States has become a gatekeeper of the Internet”. In March 2024, Meta owned five of the top ten downloaded apps worldwide. Wells Fargo has estimated Nvidia currently holds 98% of the market for data centre GPUs, critical for training the most powerful AI models.

What’s the problem for users and societies?

These gigantic platforms’ presence in the everyday lives of billions of smartphone, PC, search and social media users gives them extraordinary and unprecedented economic and social power – which, to be blunt, some of them have not used carefully.

US Senator Elizabeth Warren has warned: “Today’s big tech companies have too much power — too much power over our economy, our society, and our democracy. They’ve bulldozed competition, used our private information for profit, and tilted the playing field against everyone else. And in the process, they have hurt small businesses and stifled innovation.” The Open Markets Institute’s Barry Lynn highlighted GAFAM’s “power over the people who work for them, over capital markets and investors, and it blocks off the kind of competition that can bring innovation.”

Rather than facing competition to improve the quality of its products – on, for example, privacy, freedom of expression, and the prevalence of hate speech – Cory Doctorow calls Facebook’s users “hostages”, given the company’s relentless efforts to make it difficult for them leave. And “the more hostages they take, the more they can extract from advertisers – their true customers.” It is not the only company with this business model.

Why do digital platforms often tend towards monopoly/duopoly?

These platforms frequently claim “competition is only a click away”, and their market shares reflect the quality of their products. However, economists have found online platforms often benefit from “extreme returns to scale and scope” — their profits can increase dramatically with additional users and services.

Since platform costs are mainly fixed, such as developing software, and building relationships with suppliers and other types of customers such as advertisers, they can support millions of additional users at low additional cost-per-user, and encourage users of one service to try a related service, making use of already-gathered data. These additional users can generate further revenues and investment, which can improve the quality of service further – while smaller competitors face more expensive finance and customer acquisition costs.

With their turbocharged shares, the largest tech companies can gobble up emerging competitors like “Pac-Man” (in a vivid analogy from Rebecca Kelly Slaughter, a US Federal Trade Commissioner), spending “at least $264bn buying up potential rivals worth less than $1bn since the start of 2021 — double the previous record registered in 2000 during the dotcom boom.” As Slaughter further noted, “hundreds of smaller acquisitions can lead to a monopolistic behemoth.”

These large firms can often enter new, related markets at a great advantage to their competitors, using their knowledge of customers in one or more markets they already dominate; and use customer information from those new markets, and integration of their services, to support their existing dominant position. For example, in China, “Both Alibaba and Tencent’s efforts are centered around creating unique online ecosystems, which grant members access to their extensive resources in smartphone-based payments, big data and social media but shut out others.”

Many platforms benefit from strong “network effects”, where each new user makes the service more valuable for all existing users (since, for example, they can message or share a photo with an additional person; additional videos can be used to train more accurate object recognition algorithms for all users; or a larger customer base encourages more apps to be developed). And it may be difficult for users to switch to, or even try out, competing services, if doing so requires significant quantities of user data to be transferred, and/or they lose contact with friends and family on that platform.

What should be done in response?

The European Commission’s executive vice president, Margrethe Vestager, set out the EU’s broad position at a Princeton University event in April 2024:

In Europe, we regulate technology because we want people and businesses to embrace it. We need to bring down the old cliché that regulation goes against innovation. Quite the opposite. Laws exist to mitigate the risks, and open-up markets that have been closed down. So we can go full-on using technology. So businesses can freely innovate. And so we can mobilise the public and private investments needed to be at the edge, knowing we can trust the technology.

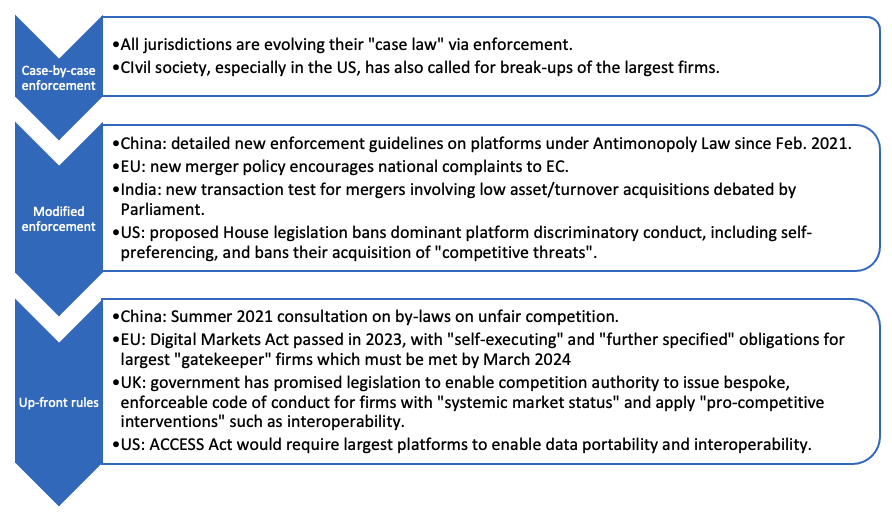

Until the mid-2020s, some competition authorities (such as Brazil’s CADE), and many competition economists, took the position that existing competition law prohibitions on “abuse of a dominant position” were capable of dealing with potential anticompetitive behaviour in digital markets, particularly as precedents developed following enforcement actions (and merger decisions) by those authorities, and the courts (some disagreed). Such cases could go as far as reversing mergers later deemed illegal, or breaking up the biggest companies, as famously happened to AT&T in the US in 1984.

But following 20+ major reviews, major jurisdictions (e.g. China, the EU, India, the UK and the US) are updating enforcement and merger rules to more explicitly take account of the characteristics of digital markets – particularly that platforms frequently buy startups much smaller than common thresholds for merger investigations, because of their future potential.

Several jurisdictions are going further (including China, the EU and the UK), putting in place new up-front rules in place specifically for the largest platforms (as also recommended by a panel of the Indian Parliament). But the US Senate has for now declined to pass legislation from the House of Representatives making such changes, beyond minor adjustments to venue and fee rules.

Those new up-front rules (sometimes imprecisely referred to as ex ante or regulation) are intended to be more specific (in terms of prohibited behaviours), general (in terms of applicability), and easily enforceable than the more general competition rules (again imprecisely often called ex post), which can sometimes take a decade for a complaint to be finally determined by the courts given their complexity and consequences – with only a narrow precedent set. Common rules under consideration include:

| Rule/enforcement | Effect | Examples |

| Data portability and interoperability | Some of the most fundamental economic drivers of digital monopolies are access to large numbers of users and their data. These requirements would enable competitors to gain access, with user consent, to data and connections – to facilitate user switching and multi-homing (simultaneous use of multiple services). Interoperability rules are already widespread in telecommunications regulation, and could allow e.g. the user of a privacy-focused social media or instant messaging service to communicate with their friends on Facebook and WhatsApp. | China, EU, UK, US |

| Limit data exploitation | Complementary to data portability, this reduces the ability of platforms without explicit user consent to combine personal data from their core services with data from their other services, track users around the web with tools like cookies and “like” buttons, or to use personal data for other purposes than it was gathered. | China, EU, Indian parliament (and enforcement against Facebook by Germany) |

| No self-preferencing | Self-preferencing bans block platforms from nudging users towards their own complementary services (such as specialised search engines) by e.g. placing those services higher in ranked results, or prominent areas of user interfaces, or as default settings; or exempting the platform’s own services from requirements placed on competitors (e.g. to display personal data usage in app store listings). | China, EU, Indian parliament, UK, US |

| No dark patterns/ manipulation of user choices | These consumer protection rules stop platforms from manipulating user decision-making through design techniques such as making one choice much easier to make than another, including using defaults and endless confirmation screens (e.g. Android’s default search engine, Google, being extremely time-consuming to change). | China, EU, UK |

| No use of platform third party seller data to compete with them | Platforms see data flowing between their different groups of customers, such as buyers and sellers on a marketplace like Amazon, or diners, restaurants, and drivers on a food delivery service like Just Eat. These rules stop platforms using this data to compete with those users, for example in deciding which own-label products or foods to sell. | China, EU, Indian parliament, US |

| Greater enforcement resources and technical expertise | While some competition authorities (including Brazil’s) have protested that existing rules against abuse of dominance and cartels are sufficient to deal with digital markets, the lack of major enforcement successes in these markets since early 2000s cases against Microsoft have been a significant factor behind the growth of today’s “hyper-scalers”. Greater resources for enforcers (including more technical experts) could begin to reverse this. | China, India, EU, UK, US |

| Adjusted enforcement rules | Setting new tests for acquisitions by platforms (such as an anticompetitive presumption for mergers involving nascent competitors in concentrated markets) and investigations by competition authorities (including making referrals easier by national EU authorities to the European Commission) could make the creation/maintenance of digital “behemoths” more difficult. | China, EU, Indian parliament, UK, US |

| Structural separation | Enforcement action can reverse previous mergers now seen as anticompetitive (e.g. Facebook’s acquisitions of GIPHY, Instagram and WhatsApp). Legislative reform could e.g. enable the FTC to order platforms to spin off specific lines of business. | China, UK, US |

Giving users genuine choice, via enabling the entry and expansion of competitors on digital markets through modified enforcement and up-front rules, can also increase the competitive pressure on platforms to better support privacy and freedom of expression. Other potential non-economic benefits of increased competition include:

- Promoting media pluralism and diversity (e.g. more incentive for news sources to offer quality news rather than seeking to maximise user attention/advertising revenues with disinformation/hate speech; addressing concerns about single firms such as TikTok significantly influencing young users’ views and carrying advertising for foreign governments).

- Improved moderation of harmful content while protecting freedom of expression (e.g. giving users a choice of moderation regimes).

- Improved social infrastructure (e.g. access and ease-of-use for users irrespective of their attractiveness to advertisers; supporting niche platforms focused on smaller linguistic and geographic communities).

- Reduced environmental impact of the online economy and Internet of Things (e.g. more incentive to offer sustainable products and reduced need to purchase multiple hardware “platforms”).

- Favouring digital sovereignty (e.g. by allowing new local market entrants to compete successfully with US/Chinese giants).

You can read more about the situation in Brazil, China, the European Union, India, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

PS In South Africa, following a two-year inquiry, the Competition Commission found in July 2023 Google “distorts platform competition”, and imposed remedies relating to self-preferencing and making South African websites more easily findable by users, as well as relating to app payments via Google and Apple’s stores. Demonstrating the global impact of EU legislative reform, it ordered both companies to implement “measures taken in Europe to comply with similar provisions in the Digital Markets Act”. It also imposed remedies on Booking.com, Uber Eats, and a number of local platforms. The Commission is now undertaking a market inquiry into news distribution on online platforms, and associated advertising technologies.