European Union

Last updated: 24 October 2023

Legislation

In 2022, the EU passed two key pieces of legislation affecting the largest technology companies:

- The goal of the Digital Markets Act (DMA) is to ensure “contestable and fair markets in the digital sector”. It contains roughly 20 separate up-front obligations (some applying to specific services) for the very largest digital gatekeeper platforms’ core services designated by the European Commission.

- The Digital Services Act (DSA) contains specific requirements for Very Large Online Platforms and Very Large Online Search Engines. It is intended to “ensure the best conditions for the provision of innovative digital services in the internal market, to contribute to online safety and the protection of fundamental rights, and to set a robust and durable governance structure for the effective supervision of providers of intermediary services.”

The scope of the two acts is similar, covering the very largest platforms operating in the EU:

| Digital Markets Act | Digital Services Act |

| “Gatekeeper” platforms (DMA Art. 3): EU turnover > €7.5bn or capitalisation > €75bn and for three years has > 45m EU users + 10,000 yearly active EU business users; Providing “core platform services” in at least 3 Member States (Art. 2.2) of: (a) online intermediation services; (b) online search engines; (c) online social networking services; (d) video-sharing platform services; (e) number-independent interpersonal communication services; (f) operating systems; (g) Web browsers; (h) virtual assistants; (i) cloud computing services; (j) online advertising services, including any advertising networks, advertising exchanges and any other advertising intermediation services, provided by an undertaking providing of any of the core platform services listed in points (a) to (i); | DSA Art. 3(g)(iii) “a ‘hosting’ service, consisting of the storage of information provided by, and at the request of, a recipient of the service” 3(i) “‘online platform’ means a hosting service that, at the request of a recipient of the service, stores and disseminates information to the public…” “Very large online platforms” and “search engines” (DSA Art. 33(1)) “have a number of average monthly active recipients of the service in the Union equal to or higher than 45 million” |

Digital Markets Act

The DMA obligations are in two lists: “self-executing” obligations in Article 5, and obligations capable of further specification by the European Commission in Article 6. The originally-proposed obligations have been summarised by Michael Veale as follows (these have been slightly updated during negotiations between the EU institutions):

| Article 5. Platforms must: | Article 6. Platforms must: |

| – Silo data relating to core services. – Not forbid businesses from using other intermediaries too. – Allow businesses to contract with users outside the platform but fulfil contracts through the platform. – Not forbid businesses from reporting them to enforcement agencies. – Not force businesses to use a particular ID service. – Not bundle their core services together and force you to sign up to 2+. AND interestingly for ads: – Provide advertisers and publishers with the price/remuneration details (to stop intermediaries controlling market visibility). | – Not use data of their business users to compete with them. – Allow end users to uninstall preinstalled software unless it is technically essential and cannot be offered standalone. – Allow installation and effective use of 3rd party software/app store using and interoperating with an OS, and allow their access by means other than through a core platform service. – Not rank their own products better than others’. – Refrain from technically restricting the ability of end users to switch between and subscribe to different apps/services to be accessed using the OS, including internet access. – Allow businesses, in the offering of ‘ancillary services’ to interoperate with OS, hardware and software. – Provide advertisers and publishers with free analysis and verification tools/information. – Provide effective data portability AND tools for end users to facilitate its exercise (normal, download your data tools exist) INCLUDING CONTINUOUS and REAL-TIME access. – Provide business users with real-time aggregated/non-aggregated data generated by end-users in their interaction with the platform. Personal data only when it relates to that business user’s services and where consent is provided. – Search engines must provide other search engine providers with anonymised “ranking, query, click and view data”.Apply non-discriminatory terms to app store terms and conditions |

Gatekeepers may apply to the European Commission for suspension of specific obligations if they would “endanger… the economic viability of the operation of the gatekeeper” (Art. 8) or for “overriding reasons of public interest” (Art. 9). And the Commission may add further obligations following a market investigation (Art. 10).

The Act came into force in spring 2023, following which the Commission initially designated six gatekeeper firms (Alphabet, Apple, Amazon, ByteDance, Meta and Microsoft) and their 22 covered “core platform services”, where the latter provide an important route for business users to reach end users. The Commission is also conducting market investigations into whether four additional services should be designated: Apple’s iMessage, and Microsoft’s Bing, Edge and Advertising.

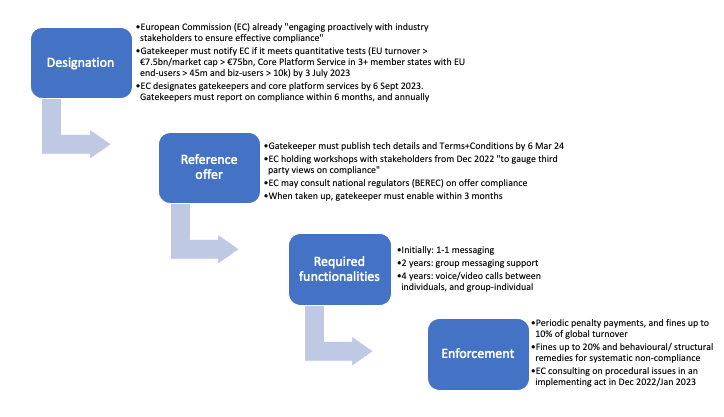

Interoperability

After much civil society campaigning, the final DMA imposes a very specific interoperability obligation on messaging/calling services (known in EU law as Number Independent Interpersonal Communications Services). Such services are required to provide a technical “interface” (likely public Application Programming Interfaces or APIs) to interested competitors for specific “basic functions”, initially one-to-one text conversations, and later group discussions and group-individual voice and video calls. (No obligations will apply to smaller services, or to users of competitors who make use of gatekeeper interoperability.)

Meta’s WhatsApp and Messenger were amongst the initial services designated, while iMessage is being investigated further. Telegram Inc. was reportedly valued below the DMA threshold at US$30-$40bn in 2021, but anyway already implements interoperability. It seems extraordinarily unlikely the non-profit Signal Foundation will ever meet the gatekeeper tests above. The final NIICS interoperability obligation explicitly protects end-to-end encryption and more broadly service security and privacy obligations.

While the European Parliament also wanted an interoperability obligation imposed on social networking services (principally Facebook), the 27 EU governments refused. However, this will be reviewed by the Commission in 2026. Until then, a related DMA obligation (Article 6(12)) will apply to app stores, search engines and SNSes, requiring gatekeepers to offer “fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory general conditions of access for business users”.

Civil society advocacy

A key civil society competition-related advocacy goal in the DMA/DSA package was to require the largest platforms to make their services interoperable with competitors. Civil society persuaded the European Commission to include an interoperability provision in its initial DMA proposal (Art. 6(1)(f)), relating to ancillary services such as payments. Since then, groups including EDRi, BEUC, Article 19, EFF and OpenForum Europe advocated the Parliament and Council extend this to the major platforms’ core services. Several such amendments, and adding similar interoperability requirements to the DSA, were proposed by centre-left and Green/Pirate parliamentarians, with some support from liberal and centre-right MEPs.

Civil society also advocated for amendments to require genuine informed consent in certain circumstances from users, restricting firms’ use of “dark patterns” in user interfaces, as well as more broadly speaking giving users more rights as opposed to focusing on business users.

Another priority for civil society is ensuring effective enforcement, increasing the resources allocated to the competition unit of the European Commission and potentially involving national regulators.

Other legislative developments

The Commission published a proposal for a Data Act in early 2022, which includes provisions “ensuring fairness in how the value from using data is shared among businesses, consumers and accountable public bodies.” The Act was agreed between the Parliament and Council in the summer of 2023. It will require operators of “smart” (Internet of Things) devices to enable customers to access all the data generated by their devices, and make it easier for users of cloud services to switch providers, as well as provide government access to data resources under specific circumstances (such as public emergencies). Two of the responsible officials provided commentaries.

The prospect of significant EU legislative reform on merger control is limited, given the preference of significant Member States such as France for industrial policy building up “European champions.” A “New Competition Tool” (similar to the UK’s powerful “market investigations”) envisaged by the Commission as part of the DMA/DSA package disappeared from the final proposals (apparently after facing serious political opposition from major European retailers and telecoms firms). Germany published a legal opinion arguing merger control measures could be included in the Digital Markets Act, but other member states, and some academics, argued the DMA’s internal market harmonisation legal basis ruled this out. Germany’s (Green party) junior minister for competition policy has restated his government’s preference for a more structural approach, and included it in a revision of the country’s competition law.

Instead, the Commission has since 19 February 2021 (before its updated merger guidance was even published) used its discretion under the Merger Regulation to encourage member states to refer cases that would not meet EU or even national turnover requirements, but “where the turnover of at least one of the companies concerned does not reflect its actual or future competitive potential. This could be the case of a start-up or recent entrant with significant competitive potential or an important innovator. It can be also the case of an actual or potential important competitive force, or of a company with access to competitively significant assets or with products or services that are key inputs or components for other industries.”

Key enforcement actions

On 25 Sept. 23, the European Commission blocked the acquisition by Booking of eTraveli (which was previously accepted by the UK Competition & Markets Authority (CMA)), since “By increasing traffic to and sales by Booking’s platforms, the transaction would have reinforced network effects and increased barriers to entry and expansion, making it harder for competing online travel agencies to develop a customer base capable of supporting a hotel OTA business.”

The European Commission also has ongoing in-depth investigations into proposed acquisitions of iRobot by Amazon (previously cleared by the UK’s CMA); Figma by Adobe; and a joint venture between Orange and MasMovil. It is investigating complaints against Apple (Pay and rules for games, e-books and music streaming apps), Facebook (Marketplace), Google (adtech) and Microsoft (for bundling Teams with Office).

Germany’s Federal Cartel office (Bundeskartellamt) has important ongoing cases against Meta and Google. In the former, it now has backing from the Court of Justice of the EU that breaches of data protection law (GDPR) can constitute abuses of a dominant position, and Meta is required to obtain users’ explicit consent before using that data. In the latter, the office has used powers from revised German competition law to order Google to obtain consent from users before sharing data between its various services (and third-party services) not covered by the Digital Markets Act, mirroring DMA provisions covering core platform services. The office announced: “Via the choice options provided to users we can curb Google’s data-driven market power and protect the users’ right to determine the use of their data.”

Acknowledgment: this update was commissioned by Open Society Foundations.

Recent Comments