Generative Interoperability: Building Online Public and Civic Spaces

I’ve been reading this excellent new report from Commons Network and Open Future, which looks at the broader implications and possibilities of interoperability in “platformised” societies:

The principle is sound, but needs to be introduced as part of a more complex set of policies that aims to ensure that outcomes of interoperability will be beneficial and meet societal objectives. The purpose of interoperability policies should be the creation of conditions for re-building the internet as a digital public space.

Tarkowski, Bloemen, Keller & de Groot (2022, p.10)

Here’s the 90-minute discussion we had on the report:

One focus on the report is the potential for interoperability to link up today’s predominantly private spaces online, run by some of the world’s largest companies, with non-commercial spaces and institutions such as public libraries, broadcasters and universities.

A second is a need for “a European mission to build the digital public space: supporting the commons, decentralizing infrastructure, strengthening public institutions and ensuring self-determination.” This “generative” interoperability is a much more comprehensive approach than the “one-dimensional” focus on “competitive” interoperability, which “fails to consider societal outcomes” (p.11).

The report rightly notes interoperability should not be an end in itself, but rather part of a comprehensive regulatory approach (which Chris Marsden and I wrote about in detail in our 2013 book Regulating Code) with a social purpose. Otherwise it can facilitate competition on harmful behaviour (like the current privacy-invasive cesspit of the adtech ecosystem).

Rather than just opening up existing dominant platforms, “generative interoperability” would be a “starting point for building and managing new, open ecosystems that serve as alternatives to the current platform economy” (p.17). Such policies would stop existing dominant platforms from “leverag[ing] open infrastructures, and then hold[ing] on to centralized power by building closed, non-interoperable solutions on top of them.”

The building blocks of this approach would be:

- Embrace an ethic of cooperation and enable trust: “people and communities, not rules, make systems interoperable and interdependent” (p.23).

- Foster peer production of shared systems, “in particular, into supporting means for shared design, creation and stewardship of broadly understood code and infrastructure that underlie the digital public space” (p.24). I think this is particularly relevant to the eIDAS Regulation update the EU is drafting, relating to digital identity tools (which are also mentioned in the almost-finalised Digital Markets Act). Another interesting example is BBC R&D’s experiment with personal data stores.

- Address power issues through governance: “Standard setting and governance of standards should be conducted by a dedicated public service entity. This agency would also be responsible for securing and managing public funding, and coordinating research and innovation efforts” (p.25). This would be a “third way” compared to intergovernmental standards bodies, such as the ITU, and private-sector led bodies such as the IETF and W3C.

- Invest in public infrastructure and new economies: “Fostering alternatives in the face of deeply undemocratic platform giants and huge concentration of wealth means investing not just in regular start ups, but specifically in business models with diverse ownership models geared towards the needs of communities and local economies” (p.25).

- Collective action to build the digital public space: “funds are needed in particular to support necessary innovation and development of public interest technologies and infrastructures. Such a program would finance initial growth of digital infrastructures and promote cooperation on research and innovation” (p.26).

I strongly agreed with the report’s identification of the problems of interoperability obligations for dominant platforms to open up APIs to competitors, rather than to support open standards. This has been a key policy battle in the development of the Digital Markets Act, where incumbent lobbying has apparently persuaded many policymakers that open APIs are sufficient. But the consequence of that is “[w]e would then no longer be faced with walled gardens, but end up facing pastures that are still enclosed by barbed wire at their borders” (p.19).

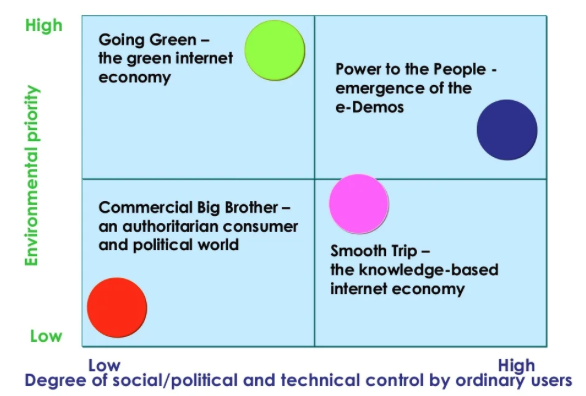

Overall, I think this is a compelling report with a range of important recommendations the EU could implement to radically transform the potential of online spaces in European society (with several similarities to the “power to the people” scenario we identified in our Towards a Future Internet report for the Commission in 2010, rather than the “commercial Big Brother” scenario we are unfortunately currently closer to):

Alongside a comprehensive interoperability obligation in the Digital Markets Act, let’s hope we see much of this ambitious programme put into practice!