Initial comments on the EU Commission’s final GDPR adequacy decision on the UK

Yesterday, I was sent the EU Commission final draft adequacy decisions on the UK (one on GDPR adequacy and one on Law Enforcement Directive adequacy). This post contains my first thoughts on the GDPR adequacy decision.

UK MASS SURVEILLANCE

The first point to note is that the Commission failed to look seriously and critically at UK surveillance in particular. Rather, the entire section in the GDPR adequacy decision on “government access” to transferred data (section 3, paras. 112—272 on pp. 30—86, i.e., 57 pages, more than 60% of the whole decision) consists of the UK’s self-valedictory self-description of its surveillance regime. The Commission does not in any way analyse this mass of information. Rather, it simply concludes:

[O]n the basis of the available information about the United Kingdom legal order, the Commission considers that any interference with the fundamental rights of the individuals whose personal data are transferred from the European Union to the United Kingdom by United Kingdom public authorities for public interest purposes, in particular law enforcement and national security purposes, will be limited to what is strictly necessary to achieve the legitimate objective in question, and that effective legal protection against such interference exists.

para.275

There is no attempt at critical analysis.

The UK write-up in many places refers to the ECtHR Big Brother Watch judgment (mainly to point out where the Court held UK law to be compliant with the Convention, see footnotes 269, 294, 365, 385, 441 and 505, and para. 269), but without explicitly mentioning that the Grand Chamber held other aspects of the UK regime (as it was when examined by the Court) to be in violation of the ECHR. It merely notes, in a footnote, that in respect of the non-ECHR-compliant aspect of the regime:

It is important to bear in mind that this judgment concerned the previous legal framework (RIPA 2000) that did not contain some of the safeguards (including prior authorisation by an independent Judicial Commissioner) introduced by the IPA 2016.

footnote 379

The Commission did not bother to check whether the new rules now actually do meet the ECHR standards — it just took this oblique reference at face value.

More importantly, there is nowhere an attempt to assess the UK surveillance regime against the stricter case-law of the CJEU which, unlike the Strasbourg Court, does not accept that it is within the margin of appreciation (or in the Luxembourg terminology, margin of discretion) of a state to decide whether or not to engage in indiscriminate bulk collection of personal data (in particular communications data), for national security purposes. In this crucial respect, the Commission therefore effectively ignores the CJEU’s Schrems II judgment.

THE IMMIGRATION EXEMPTION

On another main point of contention, the “immigration exemption” in UK law, there is what appears to be a last-minute exemption (note the square brackets at the beginning and the end of the paragraph that were still in the text I received):

[This conclusion [that ‘the United Kingdom ensures an adequate level of protection for personal data transferred within the scope of Regulation (EU) 2016/679 from the European Union to the United Kingdom’] does not concern personal data transferred for United Kingdom immigration control purposes or which otherwise falls within the scope of the exemption from certain data subject rights for purposes of the maintenance of effective immigration control (the “immigration exemption”) pursuant to paragraph 4(1) of Schedule 2 to the UK Data Protection Act. The validity and interpretation of the immigration exemption under UK law is not settled following a decision of the UK Court of Appeal of 26 May 2021. While recognising that data subject rights can, in principle, be restricted for immigration control purposes as ‘an important aspect of the public interest’, the UK Court of Appeal has found that the immigration exemption is, in its current form, incompatible with UK law, as the legislative measure lacks specific provisions setting out the safeguards listed in Article 23(2) of the United Kingdom General Data Protection Regulation (UK GDPR). In these conditions, transfers of personal data from the Union to the UK to which the immigration exemption can be applied should be excluded from the scope of this Decision. Once the incompatibility with UK law is remedied, the immigration exemption should be reassessed, as well as the need to maintain the limitation of the scope of this Decision.]

para.6, underline added

This makes no sense: the immigration exemption does not apply to personal data that are processed for immigration purposes, or transferred from the EU to the UK for immigration purposes, but to any data held by any UK public authority. Proper application of this exemption would mean that no personal data can be freely transferred from the EU to the UK if the exemption may be applied to those data. That would cover almost any personal data sent to any UK public sector entity (local councils, hospitals, etc.). My guess is this carve-out will be ignored — and is intended to be ignored.

ADEQUACY UNDER UK AND EU LAW & ONWARD TRANSFERS

The draft also effectively ignores the fact that the UK has declared Gibraltar to provide “adequate” protection under UK data protection law, even though the EU has not held that the territory provides “adequate” protection under the EU GDPR. The UK power to issue its own adequacy decision is mentioned in passing in footnote 22 (on p. 5), but without comment or analysis. The decision elsewhere mentions:

[A]s of the end of the transition period, certain transfers of personal data are treated as if they are based on adequacy regulations. These transfers include transfers to an EEA State, the territory of Gibraltar, a Union institution, body, office or agency set up by, or on the basis of the EU Treaty, and third countries which were the subject of an EU adequacy decision at the end of the transition period. Consequently, the transfers to these countries can continue as before the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the EU.

para. 81, underline added

The Commission simply ignores the implication: that if the UK is held to provide “adequate” protection by the EU, personal data transferred to the UK can be freely onwardly transferred to Gibraltar, even though Gibraltar is not deemed to provide adequate protection by the EU. That is a dereliction of duty on the part of the Commission, given that the GDPR expressly requires the Commission to include onward transfers in its assessment (Article 44). Rather, the Commission grandly states:

[A]s regards the future evolution of the United Kingdom’s international transfers regime – through the adoption of new adequacy regulations, the conclusion of international agreements or the development of other transfer mechanisms – the Commission will closely monitor the situation, assess whether the different transfer mechanisms are used in a way that ensures the continuity of protection, and, if necessary, take appropriate measures to address possible adverse effects for such continuity. … As the EU and the United Kingdom share similar rules on international transfers, it is expected that problematic divergence could also be avoided through cooperation, exchange of information and sharing of experience, including between the ICO and the EDPB.

para. 82

This mention of “close monitoring” of “new” adequacy decisions that may be issued by the UK belies the fact that the Commission ignored the actually already issued UK adequacy decision on Gibraltar. Presumably, the Commission does not regard this as a “problematic divergence” — but it does not explain why this is so “unproblematic”.

DIVERGENCE GENERALLY

On divergence on data protection more generally, it is notable that the UK already feels emboldened to signal that it wants to significantly depart from the EU rules. A UK Government-commissioned report released while the EU adequacy decisions are formally still pending, Report of the Taskforce on Innovation, Growth and Regulatory Reform (TIGRR), states:

[The EU] GDPR is prescriptive, and inflexible and particularly onerous for smaller companies and charities to operate. It is challenging for organisations to implement the necessary processes to manage the sheer amounts of data that are collected, stored and need to be tracked from creation to deletion. Compliance obligations should be more proportionate, with fewer obligations and lower compliance burdens on charities, SMEs and voluntary organisations.

para. 207

Can we really trust the Commission’s pledge that it will “closely monitor” any such “lessening of burdens” and limiting of compliance? To judge by this flimsy UK adequacy decision, not an inch.

NEXT (FINAL) STEPS

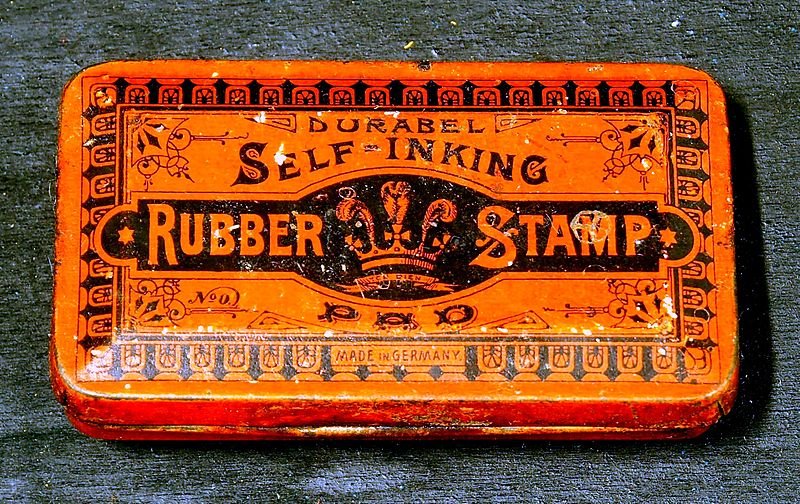

The final draft decisions were sent to the Article 93 Committee of member states’ government representatives a few days ago, with an extraordinarily tight deadline of 16 June (yesterday). It is highly likely that the Committee will rubber-stamp the final drafts (they may already have done so, or let it pass by not objecting). This means they will come into force upon publication in the Official Journal. The European Parliament cannot block them, or even refer them to the Court.

CHALLENGES ANYONE?

The only way to challenge the decision including the GDPR one, is explained in the decision, with reference to Schrems II, as follows:

[P]ursuant to Article 58(5) of Regulation (EU) 2016/679 [the GDPR] and as explained by the Court of Justice in the Schrems judgment , where a national data protection authority questions, including upon a complaint, the compatibility of a Commission adequacy decision with the fundamental rights of the individual to privacy and data protection, national law must provide it with a legal remedy to put those objections before a national court which may be required to make a reference for a preliminary ruling to the Court of Justice.

(para. 280, with reference to para. 65 in the Schrems II judgment).

It is to be hoped that someone — again good old (young) Max Schrems? — will initiate such a challenge ASAP, but it will take some time to have effect. In the meantime, EU data subjects are stuck with a decision that fails to protect them against UK mass surveillance or denial of rights in immigration contexts, while businesses cannot properly plan because the EU adequacy decision is built on sand and one day will (like the Safe Harbour and the Privacy Shield decisions) be washed away.

One thought on “Initial comments on the EU Commission’s final GDPR adequacy decision on the UK”