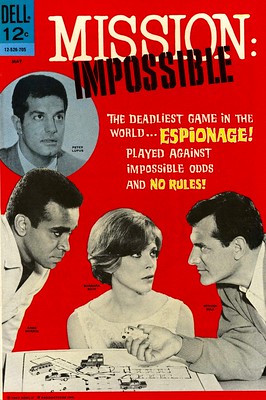

Transfers of personal data from the EU… not a “Mission Impossible”

The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which came into application on 25 May 2018, lays down even stricter rules and conditions on the transfer of personal data from the EU to non-EU countries (so-called “third countries”) (hereafter: “data transfers”) than its predecessor, the 1995 EC Data Protection Directive. The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) has moreover strictly interpreted those rules and conditions, both in relation to transfers based on “adequacy decisions” and in relation to transfers based on standard contract clauses (SCCs). This short paper provides an overview of the resulting data transfer regime.

To that end, it first briefly explains, in section 2, the European view of data protection as a fundamental, universal human right – because that is why the EU legislator and Court feel they have to impose those strict rules and conditions on data transfers. After a brief introduction to the GDPR generally, Section 3 sets out the specific rules and conditions on data transfers. Section 4 provides a summary and conclusions.

The paper is drawn up in the context of a general review of the “adequacy decisions” of third countries issued under the 1995 Data Protection Directive – such a review being required by the GDPR (Article 97) – and of the proposed issuing of an adequacy decision on the United Kingdom, which after “Brexit” is now a third country.

In that latter context (but in fact also earlier, in relation to previous adequacy decisions: see below), it has become clear that there is considerable tension between the legal requirements for adequacy decisions under the GDPR – which are strict – and the desire on the part of the European Commission to issue positive adequacy decisions to major EU trading or security partners. In relation to two draft opinions of the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) on the adequacy of the UK post-Brexit data protection regimes (i.e., the general regime and the law enforcement regime), it was reported that the Commission criticised the draft opinions for being too critical of the UK data protection standards, saying that:

If adopted without being significantly rebalanced, these opinions will be welcomed by those who … will use these critical opinions to show that our model is not credible as a global solution and that adequacy is basically a ‘mission impossible’ …

European Commission

In other words, whatever the law – and the Court – says, the Commission feels the rules should not be too rigidly or too restrictively applied, as that would hamper trade and other cooperation.

This follows on from earlier embarrassments on the part of the Commission, when the Court invalidated first the EU – US 2000 Safe Harbour adequacy decision (in its Schrems I judgment)5 and then its successor, the 2016 Privacy Shield decision (in its Schrems II judgment). Both were adopted in spite of major concerns about the adequacy of US privacy law as applied (or not) to EU personal data, and the latter in particular in spite of major concerns about the massive global US surveillance operations exposed by Edward Snowden in 2013, and the manifest lack of safeguards in US law in relation to these.

But also before then, the Commission has had a tendency to adopt positive adequacy decisions on third countries even though it was highly doubtful, even at the time, whether those countries really did provide “adequate” protection, even by the then-applicable standards. What is more, contrary to its official assurances at the time of adopting those decisions that it would closely monitor the laws and practice in the relevant third countries, to see if standards did not drop below the EU ones, and the obligation to review the earlier decisions under the GDPR after that regulation was adopted in 2016, the Commission never actually reconsidered its decisions – even if it was obvious that a third country did not provide adequate protection in terms of relevant Court judgments.

The Commission also does not appear to be in any hurry in carrying out the mandatory reviews required under the GDPR either: the Regulation was adopted on 27 April 2016, came into application on 25 May 2018 and the Commission should have examined the adequacy decisions issued under the 1995 Directive by 25 May 2020 (Article 97 GDR), but no information on any such reviews has to date been made public.

This paper therefore unapologetically takes the legal view. It explores what the GDPR provisions on data transfers, as interpreted by the Court of Justice, require for an adequacy decision. If the Commission were to adopt adequacy decisions in relation to third countries that do not meet those requirements, those decisions may well be invalidated by the Court(irrespective of whether the Commission managed to “persuade” the EDPB and the European Parliament to not be too “demanding” in this respect) – just as the EU – US Safe Harbour- and Privacy Shield decisions were. From a rule of law perspective, such judgments should be welcomed rather than ignored or disparaged.